© 2013. AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes

The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, with funding from The SCAN Foundation, is undertaking a series of studies to assess the aging population’s personal experiences with long-term care in the United States. The second study in the series, released in May 2014, surveyed Americans age 40 or older and detailed who is providing and receiving long-term care, how caregiving impacts family relationships and personal experiences, and which policy measures are favored to improve the long-term care system.1 The study found that 6 in 10 Americans age 40 or older have some experience with long-term care, either as caregivers, recipients of care, or financial providers of care, and those who have personal experiences with long-term care are more likely to be concerned about planning for their own long-term care and less likely to think they can rely on family as they age.

In addition to understanding perceptions about long-term care at the national level, another objective of the 2014 study is to gain a better understanding of how Hispanics in the United States cope with the various aspects of aging and prepare for their own long-term care, and how their experiences compare with other Americans. Census projections indicate that the Hispanic population in the United States will more than double by the year 2060, far outpacing the growth of the non-Hispanic population. By 2060, Hispanics are expected to comprise about 21 percent of the U.S. population age 65 and older.2

As this growing population ages, it will greatly impact the national dialogue on how to plan for and finance high-quality, long-term care in the United States.

Providing research and data to inform that dialogue, the AP-NORC Center’s 2014 national survey included an oversample of Hispanics age 40 or older. While Hispanics and non-Hispanics share many of the same long-term care perceptions and experiences, several key differences between these populations emerge. The survey also reveals a number of demographic differences within the Hispanic community, suggesting that Hispanics’ experiences with long-term care in the United States are nuanced.

Key findings from the 2014 study about Hispanics’ experiences with long-term care in the United States are summarized below:

- A majority of Hispanics age 40 or older have experience with long-term care, either as a caregiver for a family member or close friend, a care recipient, or as someone who pays to provide in-home, ongoing living assistance.3

- Hispanics age 40 or older who have provided ongoing living assistance for a family member or close friend are more likely than non-Hispanics to say their experience was positive, and are less likely to say their experience caused stress in their family.

- Hispanics age 40 or older anticipate needing long-term care at a higher rate than other Americans, yet only 1 in 10 report planning for this necessity.

- Annual household income is a major factor in whether or not Hispanics have planned for future ongoing living assistance need, more so than for other Americans.

- As with non-Hispanics, Hispanics age 40 or older lack confidence in their ability to pay for ongoing living assistance. Just 1 in 5 is confident they will have the financial resources to pay for any care they may need as they age.

- Hispanics age 40 or older anticipate needing support from Medicaid for ongoing living assistance at a significantly higher rate than non-Hispanics.

- Similar to non-Hispanics, a majority of Hispanics support 4 of the 5 policy proposals that may help Americans prepare for the costs of long-term care, though the level of support differs between the two groups.

Hispanics provide ongoing living assistance at similar rates to non-Hispanic Americans, yet they are more likely to reflect positively on their experiences providing care, and less likely to say it has caused stress in their family or taken time away from their family life.ꜛ

The survey shows that Americans’ experiences with long-term care are diverse and span a number of socioeconomic and other demographic factors. Like non-Hispanic Americans, a majority of Hispanics age 40 or older (60 percent) have experience providing, receiving, or financing long-term care services. Fifteen percent of Hispanics are currently receiving, or have ever received, ongoing living assistance.

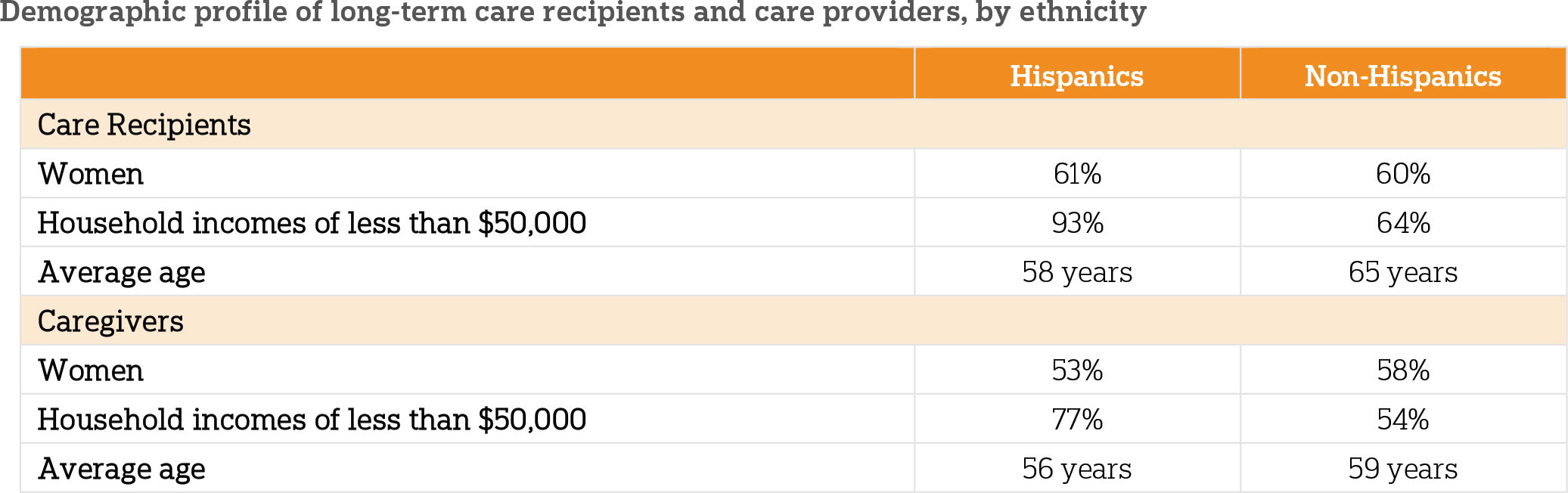

Similar to other Americans, Hispanics receiving care tend to be women, but they also tend to be younger and have lower incomes than other Americans receiving care. Six in 10 Hispanics who have experience receiving ongoing living assistance are women. Hispanic recipients of care are more likely than non-Hispanic care recipients to have household incomes of less than $50,000 (93 percent vs. 64 percent of non-Hispanics). Hispanic care recipients are also younger on average (58 years old) than non-Hispanic care recipients (65 years old).

Providers of care among Hispanics and non-Hispanics are mostly women, but Hispanics again tend to be younger and have lower incomes than non-Hispanic caregivers. About half of Hispanics age 40 or older (51 percent) are currently providing, or have ever provided, ongoing living assistance to a family member or close friend on a regular basis. Seventy-seven percent of Hispanic caregivers have a household income of less than $50,000, compared to 54 percent of non-Hispanic caregivers. Hispanic caregivers are an average age of 56, slightly younger than the average non-Hispanic caregiver (59 years). Non-Hispanic women age 40 or older (57 percent) are more likely than non-Hispanic men (49 percent) to say they have experience providing care to a family member or close friend. These gender differences disappear for Hispanics (52 percent women, 50 percent men). In all, 53 percent of Hispanic caregivers are women.

Americans also experience the long-term care system through financial means. Twelve percent of Hispanics age 40 or older say they are, or someone in their family is, currently employing someone to provide in-home, ongoing living assistance services.

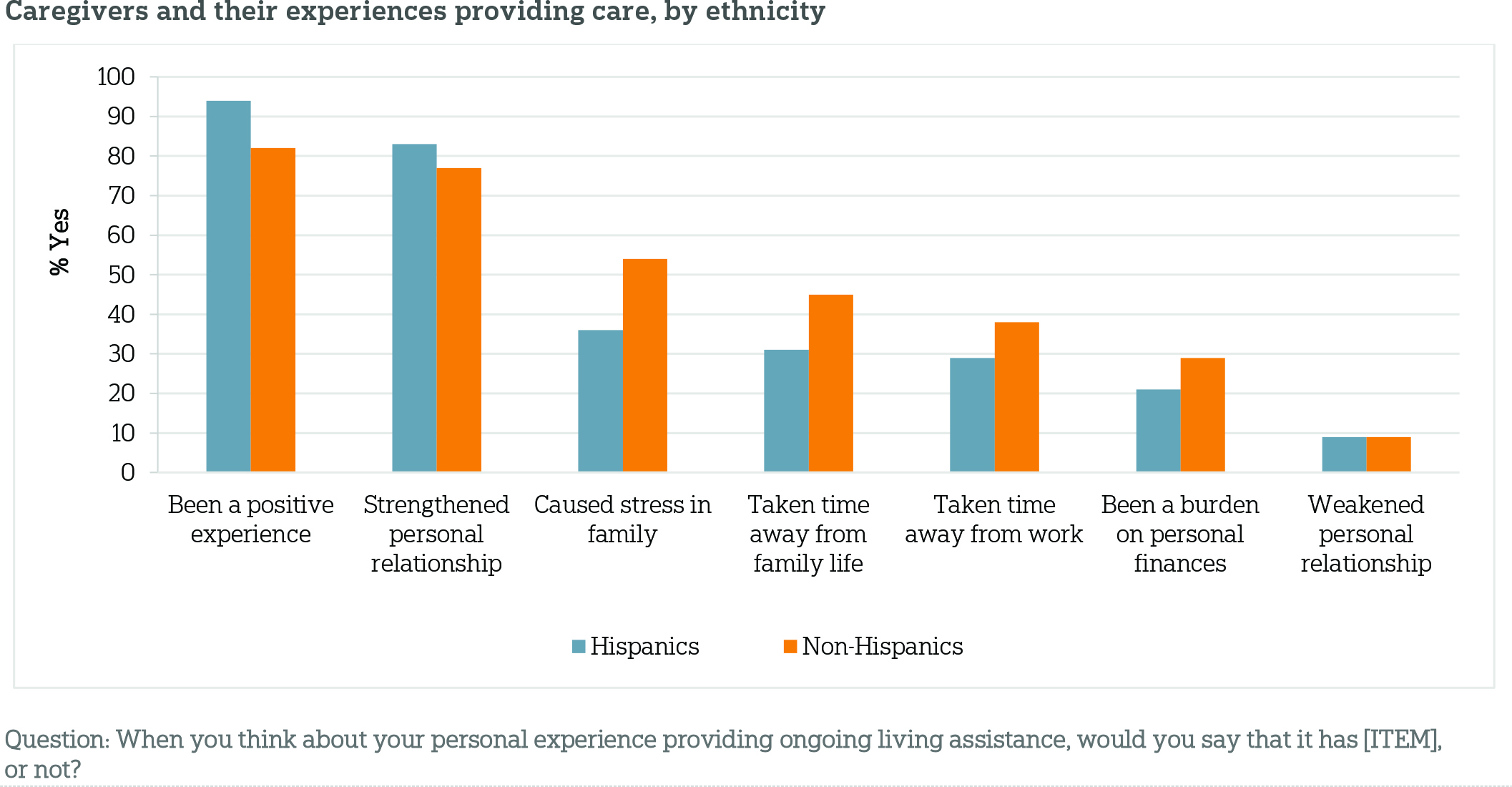

Overall, Americans age 40 or older reflect positively on their personal experiences providing assistance to loved ones, but it’s nearly universal among Hispanic caregivers. Fully 94 percent of Hispanic caregivers say it has been a positive experience in their lives, compared to fewer—82 percent—of non-Hispanic caregivers. Similar to other Americans, 83 percent of Hispanics say the experience strengthened their personal relationship with the friend or family member for whom they cared, and just 9 percent say the experience weakened their relationship.

The stress levels that result from caregiving differ sharply among non-Hispanic and Hispanic caregivers, even controlling for other socioeconomic and demographic factors. While over half of non-Hispanic caregivers (54 percent) say their experience providing ongoing living assistance caused stress in their family, far fewer Hispanic caregivers say the same (36 percent). Hispanic caregivers are also slightly less likely to say the experience was a burden on their personal finances (21 percent vs. 29 percent).

For non-Hispanic caregivers, the financial burden of providing care varies significantly by household income. Those with household incomes of less than $50,000 are more likely than those earning more to say providing ongoing living assistance is a burden on their personal finances (36 percent vs. 21 percent). However, there is no difference on the question of financial burden between income groups among Hispanics (21 percent for those with incomes of less than $50,000, 23 percent for those with incomes of $50,000 or more).

Although Hispanics anticipate personally needing ongoing living assistance as they age at a higher rate than other Americans, they are less likely to say they have taken action to plan for this assistance.ꜛ

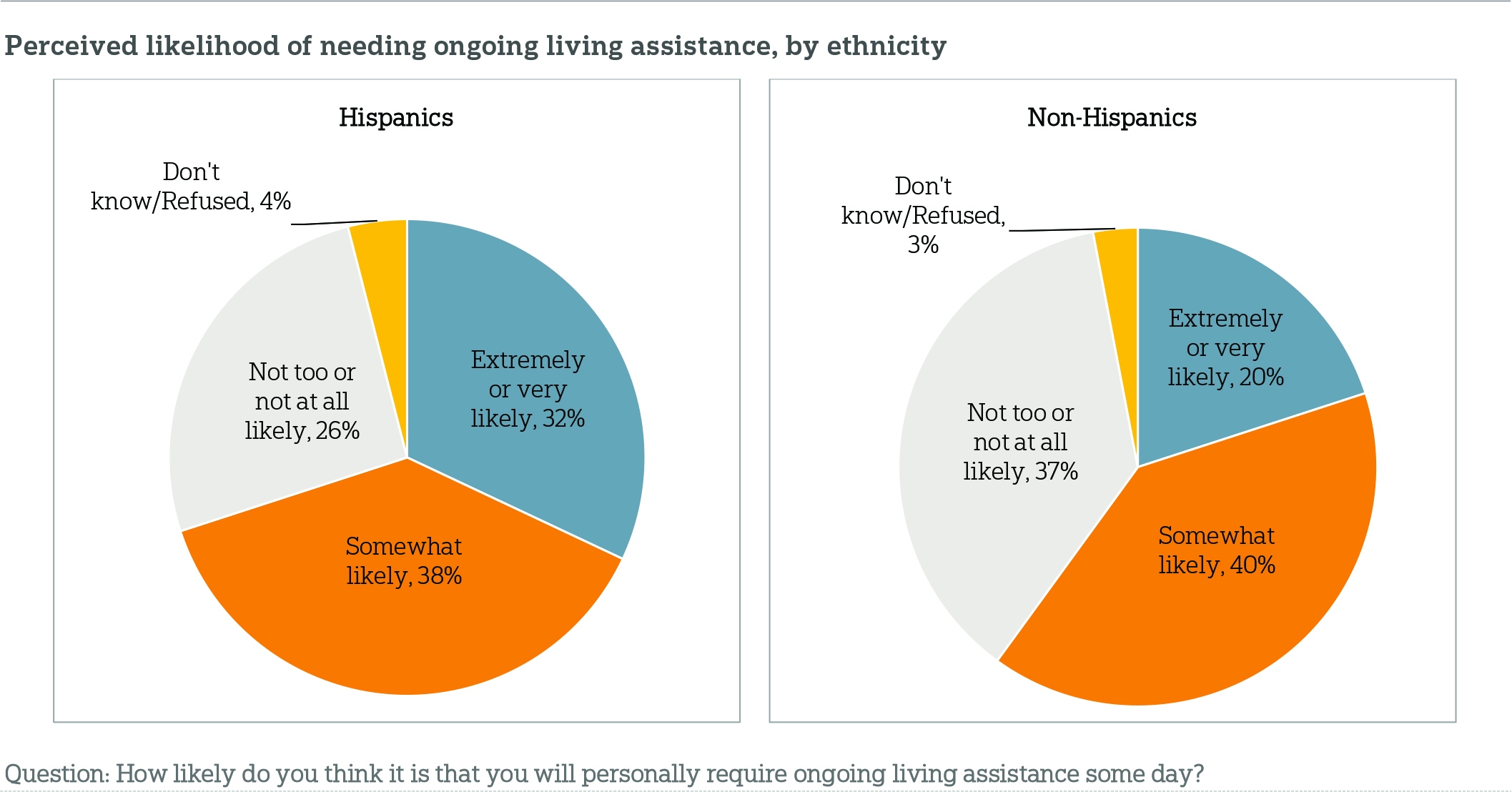

The survey shows that while Hispanics age 40 or older are more likely to need ongoing living assistance, they are less likely than non-Hispanics to have planned for such assistance. Seven in 10 Hispanics age 40 or older who are not currently receiving ongoing living assistance say it is at least somewhat likely that they will personally require ongoing living assistance someday—more than the 6 in 10 non-Hispanics who anticipate needing care. Fewer than 3 in 10 Hispanics (26 percent) say it is unlikely that they will require ongoing living assistance in the future.

Despite a solid majority believing that they will personally require living assistance as they age, few Hispanics have planned for this kind of care. Ten percent say they have done quite a bit or a great deal of planning for their ongoing living assistance needs, 16 percent have done a moderate amount, and an overwhelming majority, 73 percent, have done only a little or no planning at all.

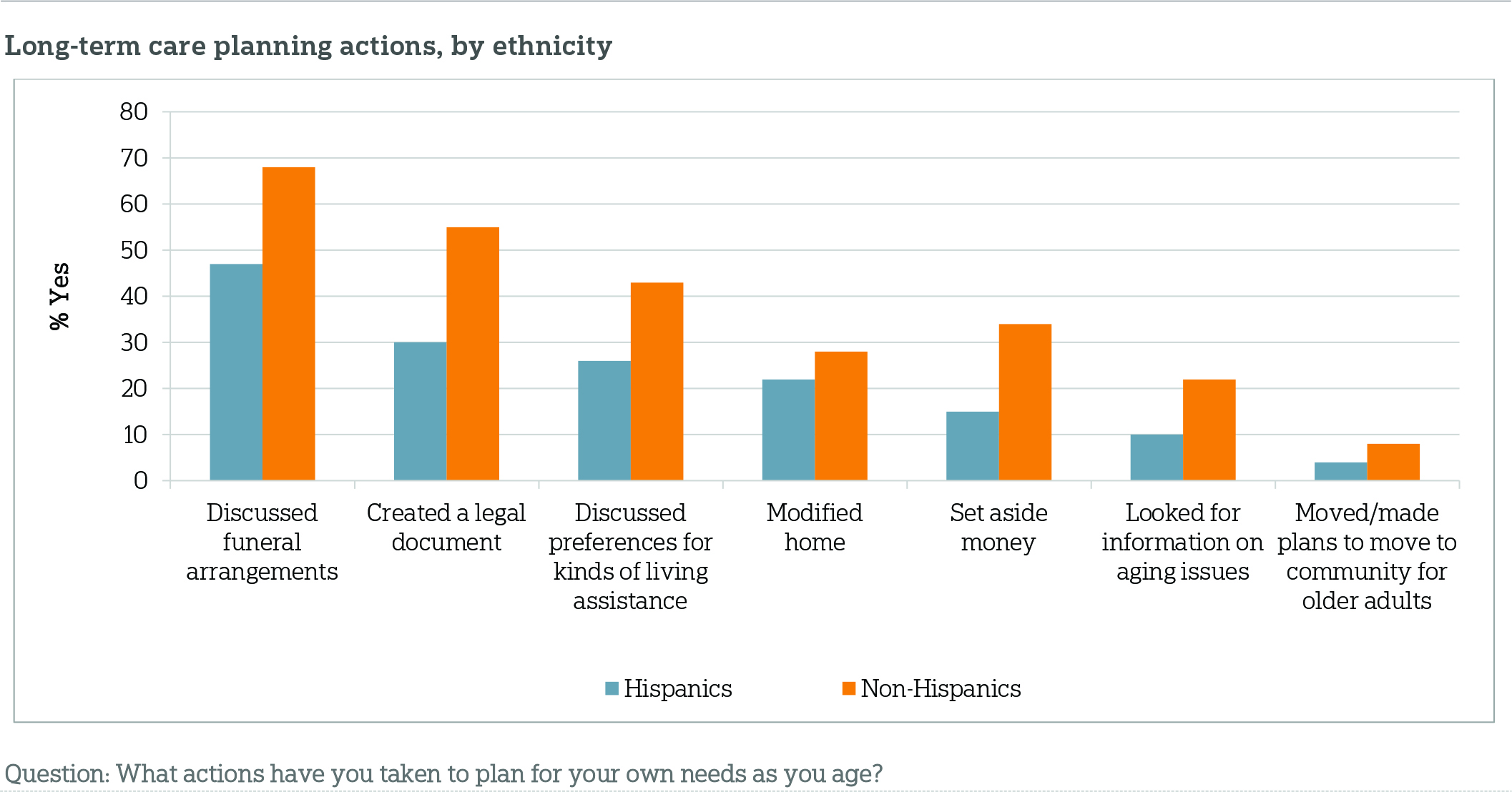

A closer look at specific actions one might take to plan for ongoing living assistance reveals more planning, but Hispanics are still less likely than non-Hispanics to report taking steps to plan for their personal needs as they age. In the survey, respondents were asked about seven individual long-term care planning actions; 87 percent of non-Hispanics age 40 or older report doing at least 1 of the 7 planning actions, compared to 65 percent of Hispanics. Hispanics are nearly three times as likely as other Americans to say they completed none of these actions (35 percent vs. 13 percent).

Specifically, on a few of these steps to address future long-term care needs or end-of-life planning, Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanics to plan ahead. For example, Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanics to report setting aside money to pay for ongoing living assistance (15 percent vs. 34 percent), discussing their ongoing living assistance preferences with a loved one (26 percent vs. 43 percent), creating a living will or advance directive (30 percent vs. 55 percent), and discussing funeral arrangement preferences with someone they trust (47 percent vs. 68 percent).

On a number of items, nonetheless, Hispanics and non-Hispanics report planning at similar rates. Comparable proportions of Hispanics and non-Hispanics report looking for information about aging, modifying their home to make it easier to live in as they age, and making plans to move into a community or facility designed for older adults.

Household income plays a significant role in the level of preparation for long-term care needs as people age. For example, Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanics to set aside money to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses such as nursing home care, housing in a senior community, or care from a home health care aide (15 percent vs. 34 percent). Even when taking household income into account, the differences remain stark. Non-Hispanics with household incomes of less than $50,000 are nearly four times as likely as Hispanics in the same income category to set aside money to pay for ongoing living assistance expenses (22 percent vs. 6 percent). Similarly, nearly half of lower-income non-Hispanics (48 percent) report creating a living will or advance treatment directive, while just 21 percent of Hispanics in the same income category have done so.

Hispanics lack confidence that they will have the necessary financial resources to pay for long-term care as they age and anticipate the need for Medicaid to cover the costs.ꜛ

Similar to the non-Hispanic U.S. population age 40 or older, most Hispanics are not very confident that they will have the financial resources to pay for the ongoing living assistance they may require as they age. Fifty percent of Hispanics age 40 or older say they are not too or not confident at all that they will have the financial resources to pay for any care they may need, 28 percent are somewhat confident, and 21 percent are very or extremely confident.

Not surprisingly, income is a clear indicator of one’s level of confidence to pay for future care. Among Hispanics, those who have annual household incomes of less than $50,000 are more than twice as likely to express lower levels of confidence in their ability to pay for ongoing living assistance (61 percent vs. 26 percent).

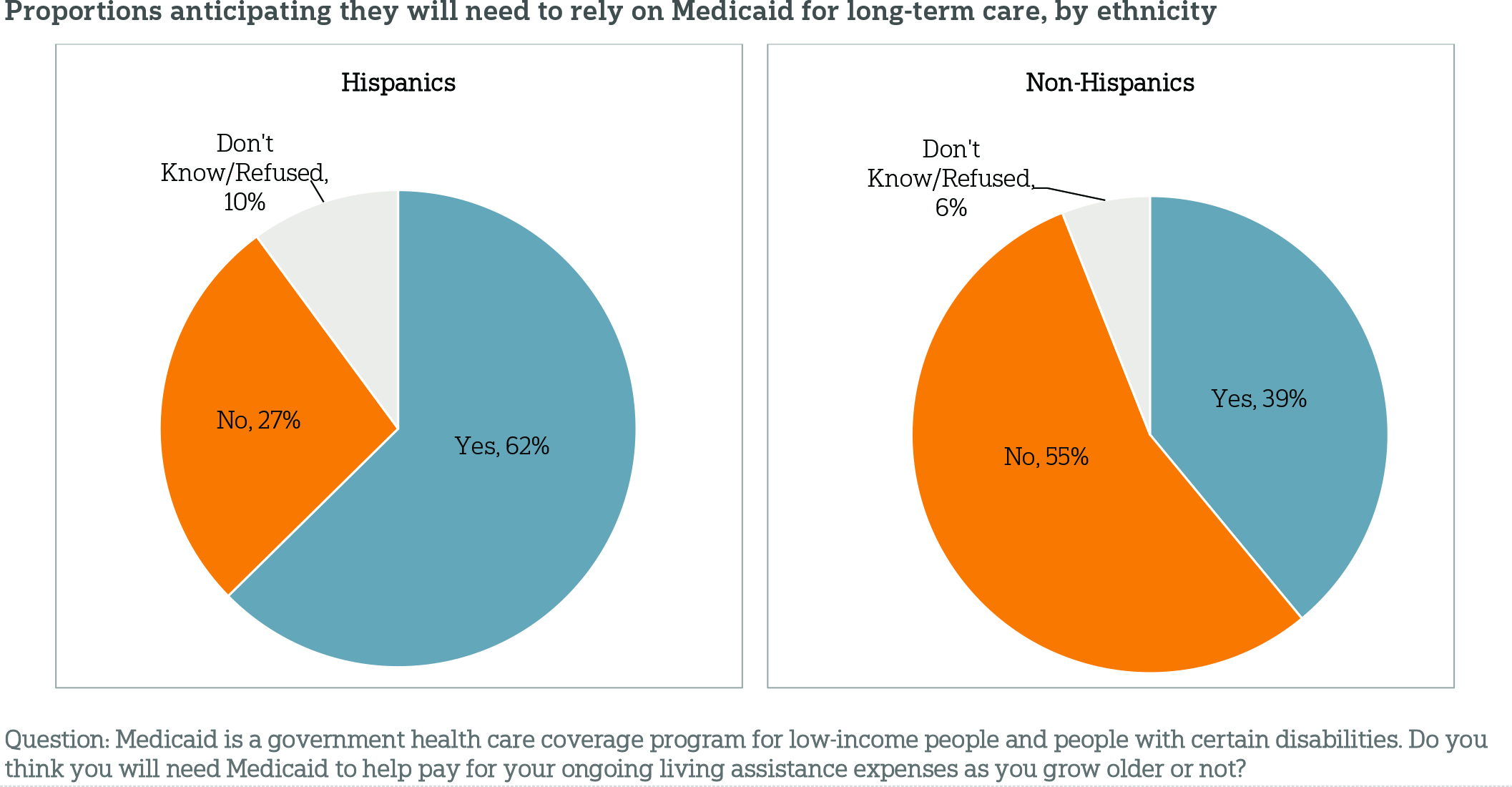

The survey also looked at Americans’ perceptions about Medicaid as it relates to long-term care, and specifically whether people age 40 or older think they will have to rely on the program for care as they age. Medicaid is a government health care coverage program for low-income people and people with certain disabilities, and it is the single largest payer for long-term care services in the United States.4 Hispanics age 40 or older are more likely than non-Hispanics to say they anticipate needing Medicaid to help pay for their ongoing living assistance expenses (62 percent vs. 39 percent). Even among Hispanics with health care coverage, a majority (59 percent) think they will need Medicaid to pay for their long-term care needs.

The differences between Hispanics and non-Hispanics in the anticipated need for Medicaid remain robust even when accounting for household income and other demographic factors. For example, 76 percent of Hispanics with household incomes of less than $50,000 say they will need Medicaid to help pay for their long-term care, compared with 58 percent of non-Hispanics in the same income category.

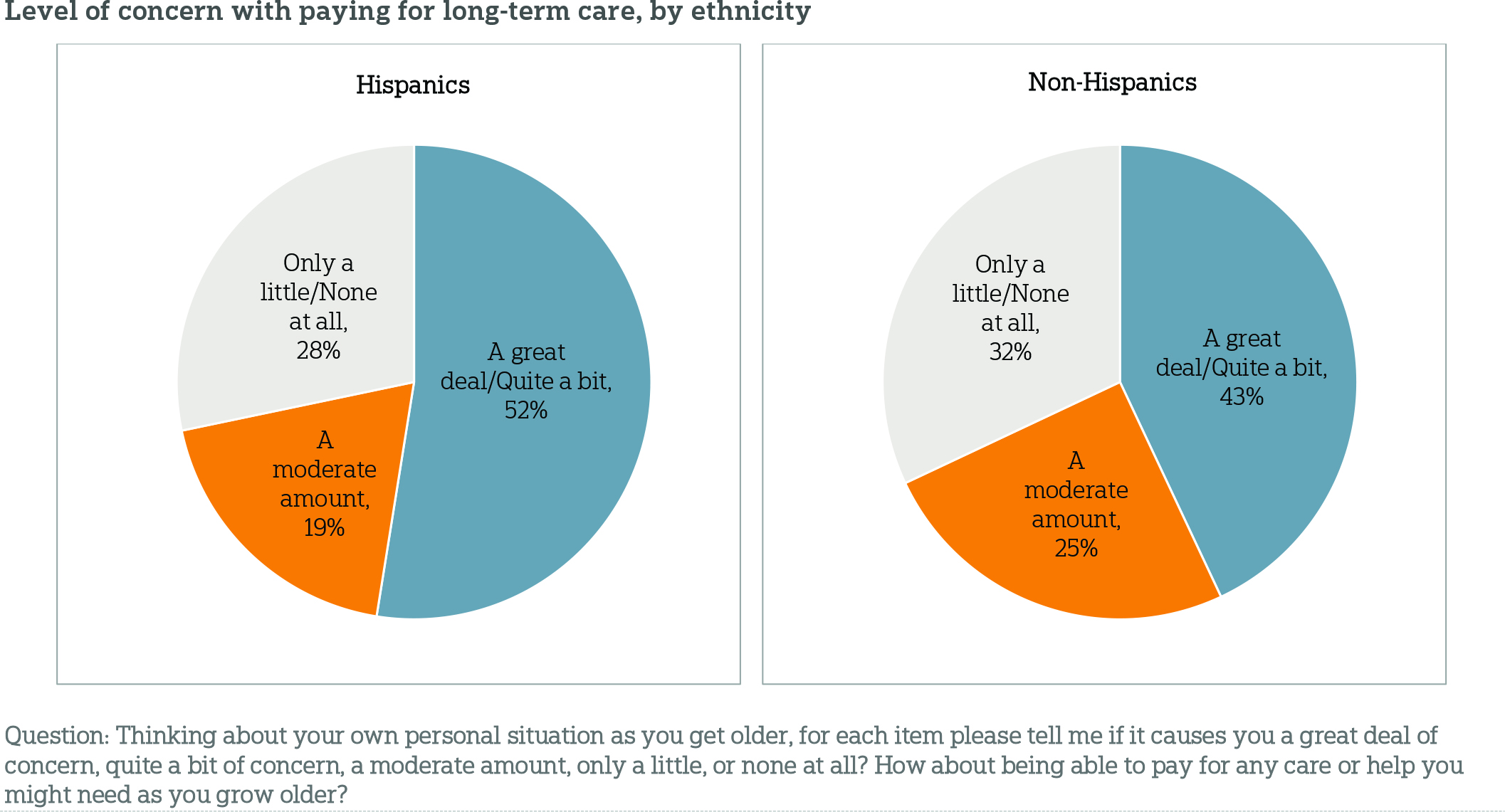

Indeed, when it comes to thinking about aging, Hispanics and non-Hispanics express similar levels of concern about most aspects of aging with one significant difference: concern about how to pay for long-term care. Fifty-two percent of Hispanics say they have quite a bit or a great deal of concern about being able to pay for any care, while 43 percent of non-Hispanics express the same concern. This difference is true even controlling for income and other demographic factors.

At similar levels, Hispanics and non-Hispanics are concerned with losing their independence, losing their memory or other mental abilities, being a burden on their family, having to move into a nursing home, not planning enough for the care they might need as they age, leaving debts to their family, or being alone without family or friends around.

Support for policies that help Americans prepare for the costs of long-term care is high among Hispanics and other Americans, yet differences in levels of support emerge between the two groups.ꜛ

The survey gauged opinion on five different policy measures that may help Americans prepare for the costs of ongoing living assistance. Like non-Hispanic Americans, large majorities of Hispanics age 40 or older express support for four of the proposals, though there are some differences in degree of support. Hispanics are less likely than non-Hispanics to favor tax breaks to encourage saving for ongoing living assistance expenses (71 percent vs. 82 percent), the ability for individuals to purchase long-term care insurance through their employer (67 percent vs. 76 percent), and tax breaks for consumers who purchase long-term care insurance (65 percent vs. 78 percent).

Hispanics age 40 or older are most divided on a requirement that individuals purchase private long-term care insurance, with 49 percent saying they strongly or somewhat favor the proposal, 26 percent saying they strongly or somewhat oppose it, and 19 percent saying they neither favor nor oppose it. Yet, Hispanics age 40 or older are more likely than non-Hispanics (32 percent) to say they favor the proposal. Hispanics are also more likely than non-Hispanics to support a policy proposal for a government administered long-term care insurance program similar to Medicare (68 percent) than non-Hispanics (57 percent).

Similar proportions of Hispanics and others have received long-term care information in the last year, but their information sources vary to a degree.ꜛ

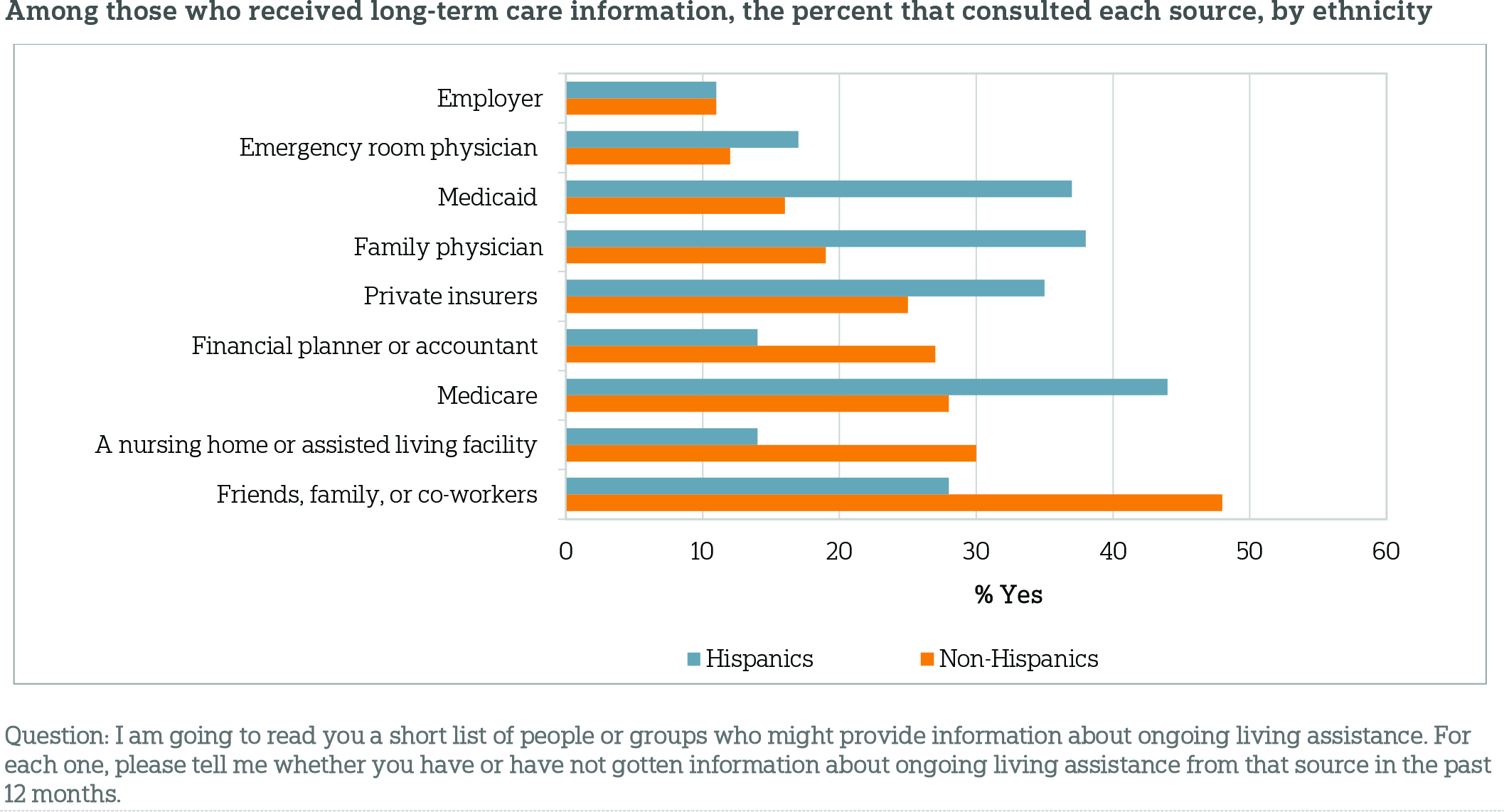

The national study showed that Americans generally lack information about long-term care, mostly get it from their friends or family, and tend to trust information from their own social network or their own doctor. On the issue of receiving little information on long-term care, results for Hispanics are consistent with the national findings. Further, 43 percent of Hispanics age 40 or older have received information about ongoing living assistance in the last 12 months from at least 1 of the 9 sources tested in the survey, similar to the proportion of non-Hispanics (46 percent).

However, Hispanics and non-Hispanics who have received information about ongoing living assistance in the last 12 months differ in terms of the types of sources they consult. Among non-Hispanics who received information, friends, family, or co-workers are the most prevalent sources; 48 percent of them say they have received long-term care information from this source, compared to 28 percent of Hispanics who received information. For Hispanics, Medicare is the most common information source; 44 percent of Hispanics who received information say they have received such information from Medicare, compared to 28 percent of non-Hispanics. Among those who have received information, Hispanics are more likely than other Americans to say they have received information in the past year from their family physician (38 percent vs. 19 percent) and Medicaid (37 percent vs. 16 percent).

Despite some differences in terms of how each of these groups obtains long-term care information, they hold similar levels of trust in each source.

About the Studyꜛ

Survey Methodology

This survey, funded by The SCAN Foundation, was conducted by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research between the dates of March 13 through April 23, 2014. Staff from NORC at the University of Chicago, the Associated Press, and The SCAN Foundation collaborated on all aspects of the study.

This random-digit-dial (RDD) survey of the 50 states and the District of Columbia was conducted via telephone with 1,745 adults age 40 or older. In households with more than one adult age 40 or older, we used a process that randomly selected which eligible adult would be interviewed. The sample included 1,340 respondents on landlines and 405 respondents on cell phones. The sample also included oversamples of Californians and Hispanics nationwide age 40 or older. The sample includes 458 Hispanics and 1,287 non-Hispanics from the 50 states and the District of Columbia age 40 or older. Cell phone respondents were offered a small monetary incentive for participating, as compensation for telephone usage charges. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish, depending on respondent preference. All interviews were completed by professional interviewers who were carefully trained on the specific survey for this study.

The RDD sample was provided by a third-party vendor, Marketing Systems Group. The final response rate was 22 percent, based on the American Association of Public Opinion Research Response Rate 3 method. The sample design aimed to ensure the sample representativeness of the population in a time- and cost-efficient manner. The sampling frame utilizes the standard dual telephone frames (landline and cell), with a supplemental sample of landline numbers targeting households with Hispanic adults. The targeted sample was also provided by Marketing Systems Group and was pulled from a number of different commercial consumer databases and demographic data at the telephone exchange level. Sampling weights were appropriately adjusted to account for potential bias introduced by using the targeted sample.

Sampling weights were calculated to adjust for sample design aspects (such as unequal probabilities of selection) and for nonresponse bias arising from differential response rates across various demographic groups. Poststratification variables included age, sex, race, region, education, and landline/cell phone use. The weighted data, which thus reflect the U.S. population, were used for all analyses. The overall margin of error for the national sample is +/- 3.6 percentage points, including the design effect resulting from the complex sample design. The overall margin of error for the Hispanic sample is +/-6.8 percentage points.

All analyses were conducted using STATA (version 13), which allows for adjustment of standard errors for complex sample designs. All differences reported between subgroups of the U.S. population are at the 95 percent level of statistical significance, meaning that there is only a 5 percent (or less) probability that the observed differences could be attributed to chance variation in sampling. Additionally, bivariate differences between subgroups are only reported when they also remain robust in a multivariate model controlling for other demographic, political, and socioeconomic covariates. A comprehensive listing of all study questions, complete with tabulations of top-level results for each question, is available on the AP-NORC Center’s long-term care website: www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Contributing Researchers

From NORC at the University of Chicago

Trevor Tompson

Jennifer Benz

Nicole Willcoxon

Emily Alvarez

From The Associated Press

Jennifer Agiesta

About the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research

The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research taps into the power of social science research and the highest-quality journalism to bring key information to people across the nation and throughout the world.

- The Associated Press (AP) is the world’s essential news organization, bringing fast, unbiased news to all media platforms and formats.

- NORC at the University of Chicago is one of the oldest and most respected, independent research institutions in the world.

The two organizations have established the AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research to conduct, analyze, and distribute social science research in the public interest on newsworthy topics, and to use the power of journalism to tell the stories that research reveals.

The founding principles of the AP-NORC Center include a mandate to carefully preserve and protect the scientific integrity and objectivity of NORC and the journalistic independence of the AP. All work conducted by the Center conforms to the highest levels of scientific integrity to prevent any real or perceived bias in the research. All of the work of the Center is subject to review by its advisory committee to help ensure it meets these standards. The Center will publicize the results of all studies and make all datasets and study documentation available to scholars and the public.

The complete topline data are available at wwww.longtermcarepoll.org.

Footnotesꜛ

1. Long-Term Care in America: Expectations and Reality. May 2014. The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. https://www.longtermcarepoll.org/Pages/Polls/Long-Term-Care-2014.aspx.ꜛ

2. Census Press Release. December 12, 2012. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html.ꜛ

3. Ongoing living assistance was defined for respondents as “assistance can be help with things like keeping house, cooking, bathing, getting dressed, getting around, paying bills, remembering to take medicine, or just having someone check in to see that everything is okay. This help can happen at your own home, in a family member’s home, in a nursing home, or in a senior community. And, it can be provided by a family member, a friend, a volunteer, or a health care professional.”ꜛ

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Who Pays for Long-Term Care? Washington, DC: DHHS. http://longtermcare.gov/the-basics/who-pays-for-long-term-care/. Accessed May 14, 2014.ꜛ