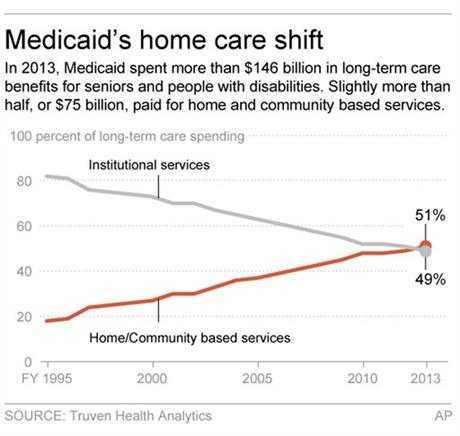

Graphic shows changes in Medicare expenditures for home- and community-based care services; 2c x 3 inches; 96.3 mm x 76 mm;

By Alejandra Cancino – Associated Press | Mon, April 4, 2016

CHICAGO (AP) — The federal government is pushing states to keep more low-income seniors out of nursing homes and, instead, enroll them in home and community-based programs.

The shift comes as demand for long-term care is rising. By 2050, the number of people older than 85 is expected to triple to more than 18 million. These seniors tend to have the highest disability rate and the greatest need for long-term care.

The tug-of-war between rising demand and controlling costs has advocates for seniors worrying about quality of care.

Medicaid is one of the largest expenses for states, and a it’s a program they look to for savings when budgets are tight. Medicaid spending on long-term care for seniors rose by 4 percent, to nearly $89 billion in fiscal year 2013.

Advocates say programs for seniors often wind up on the chopping block.

For example, Illinois is considering changes to its home and community-based program that would reduce funding by about $200 million.

“I think that oftentimes people are afraid of change, regardless of what that change is,” said Andrea Maresca, director of federal policy and strategy at the National Association of Medicaid Directors. There’s room to improve the programs, Maresca said, and states are also trying to make sure seniors don’t lose access to services.

Loren Colman, of the Minnesota Department of Human Services, said it took that state roughly 25 years to shift from institutional care to home and community-based programs. The focus now is on helping older adults remain at home, delaying expensive nursing home care and supporting family caregivers.

To rein in costs, some states are changing payment systems from fee-for-service to managed care, which generally pays a per-person rate to providers who manage seniors’ health and social services.

Gwen Orlowski, an attorney at Central Jersey Legal Services, said New Jersey’s managed care program is an improvement over its previous system, but not without issues. She’s had to help some seniors appeal service cuts.

“I do worry that the delivery of services is beholden to the money that the managed-care companies are receiving (from the state) and the money they want to make,” said Orlowski, whose office provides free legal assistance to low-income seniors.

To address fears, new federal regulations have been proposed to strengthen protections for seniors in managed care, including help with appeals. A final rule is expected this spring.

Already, states are working on implementing earlier rules from 2014 aimed at improving quality of care across programs. In exchange for federal dollars, states must ensure that seniors have a say over where they want to live, and get treated with dignity and respect.

Robyn Grant, director of public policy and advocacy for the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long Term Care, said regulations are a “step in the right direction,” but there needs to be proper enforcement. “Unfortunately, that’s very nebulous,” Grant said.

The cornerstone of home and community-based programs is personal care services, such as providing an aide who helps with cooking or cleaning. Those services cost a fraction of nursing home care.

The average per-person cost of Illinois’ Community Care Program is $860 per month, less than a third of the cost for a nursing home. Over the last decade, however, enrollment has doubled to more than 83,000 people, costing the state nearly $1 billion in fiscal 2015.

One of those seniors is Yuen Chu Wong, 71, of Chicago, who worked at a chocolate factory until she retired nearly a decade ago. Wong requested a home-care aide about seven years ago when her health began deteriorating.

The aide, Wan Ling He, does laundry for Wong and her husband, cleans the apartment and prepares traditional Chinese soups. The two women have developed a friendship, often talking in their native Cantonese about food and cooking shows. Wong calls her aide “an old friend.”

Illinois is now proposing to move about half the seniors in its program to a new initiative it says will increase flexibility while lowering costs. For example, it may pay for Uber rides to doctors’ appointments instead of sending a driver to seniors’ homes.

Lori B. Hendren, associate state director of advocacy and outreach at AARP Illinois, said the new proposal raises questions about the state’s commitment to seniors aging independently and with dignity at home.

“Where will the savings come from?” Hendren said. “The devil is in the details.”

___

EDITOR’S NOTE — Alejandra Cancino is studying health care and long-term care issues as part of a 10-month fellowship at the AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, which joins NORC’s independent research and AP journalism. The fellowship is funded by The SCAN Foundation.