Many older Americans who take on a caregiving role for an aging loved one lack the training they need to provide that care. They have limited access to programs designed to provide a break to caregivers and face difficulties in the workplace, a new poll shows. Still, the majority describe providing care as worthwhile and say caregiving has a positive impact on their life. The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research survey of Americans age 40 and older with experience either giving or receiving long-term care finds that many share caregiving responsibilities (most commonly among siblings or with a paid caregiver), but fully one-third of caregivers shoulder the responsibilities of providing assistance alone.

The survey shows that caregivers who work while providing care may face special hardships. Nearly half of working caregivers report some difficulties balancing work and caregiving responsibilities. Seventy percent have missed work to provide care to an aging friend or family member, and while most have used their sick, vacation, or personal time, many have also taken unpaid leave to provide this care. Among those who missed work to provide care, 29 percent are concerned about their job security. And some working caregivers report experiencing serious repercussions at work because of their caregiving role, including being treated differently by management or coworkers, being excluded from further job growth opportunities, and having their roles or responsibilities changed. In rare cases, some even report being asked to resign or being fired.

The majority of Americans age 65 and older will require at least some support with activities of daily living—things like cooking, bathing, or remembering to take medicine.1,2 Unpaid family members and friends provide much of the long-term care their loved ones require to remain at home in the community as they age. This survey focuses on the perspectives of these informal caregivers, as well as the experiences of some of the older adults to whom they provide care. It is a follow up to the fifth annual Long-Term Care Trend Survey,3 completed in March 2017.

This AP-NORC Center study, with funding from The SCAN Foundation, includes 1,004 interviews with a nationally representative sample of Americans age 40 and older with past or current experience providing or receiving long-term care. The sample includes 79 percent with experience providing care only, 10 percent with experience receiving care only, and 11 percent who have experience with both.4 Data were collected using NORC’s AmeriSpeak® Panel.

Key themes and findings from this study are described below:

- American caregivers provide assistance to older adults suffering from a range of limitations and ailments. Fifty-nine percent provide care to someone with limitations due to long-term physical conditions, 36 percent care for someone who needs help because of loss of memory, and 31 percent care for someone with a short-term physical condition or disease.

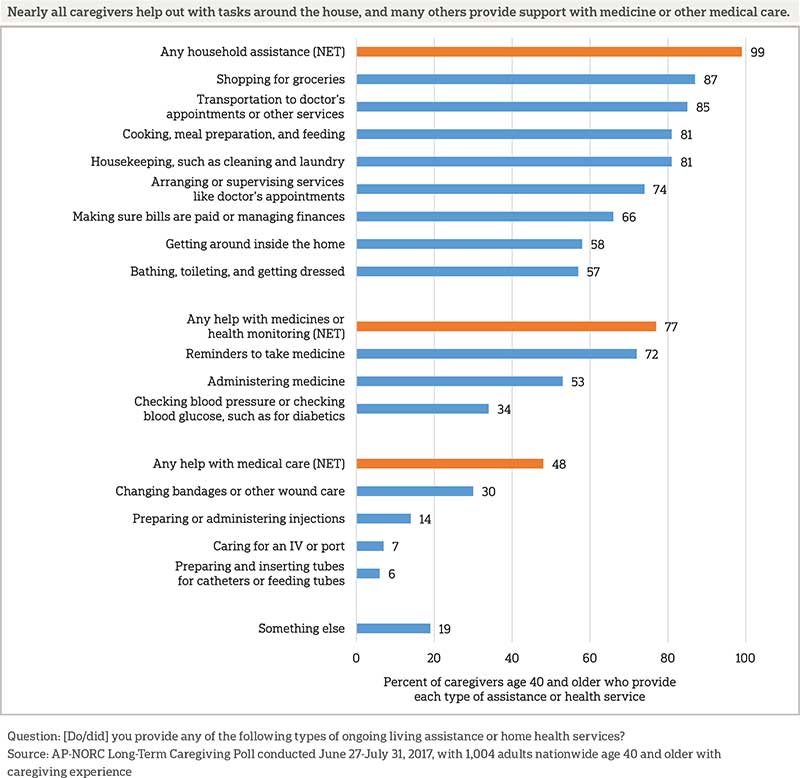

- While help shopping for groceries (87 percent) and providing transportation to doctors’ appointments (85 percent) are the most common types of assistance that caregivers provide, many provide support with medications or health monitoring such as checking blood pressure, and some also provide forms of clinical medical care such as changing bandages or preparing or administering injections.

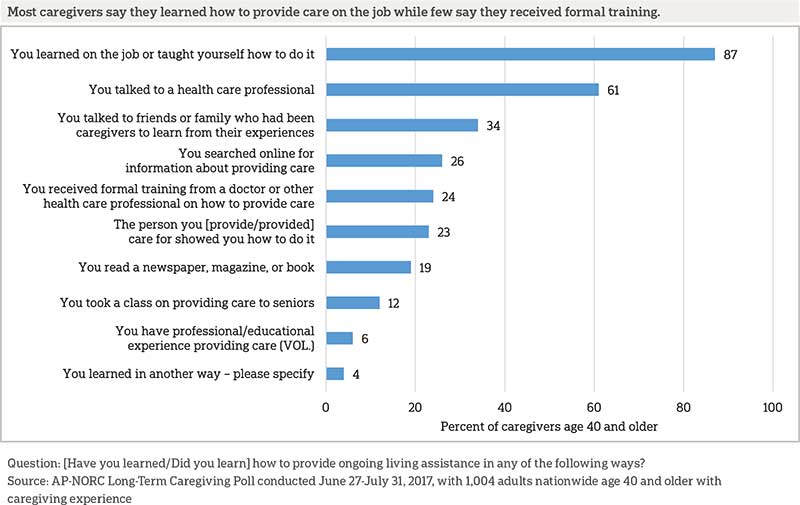

- Sixty-one percent of caregivers talked to a health care professional to learn how to provide care, but only 24 percent received formal training from a doctor or other health care professional.

- Over half of caregivers feel undertrained, and 28 percent say they received hardly any or none of the training they needed to provide care.

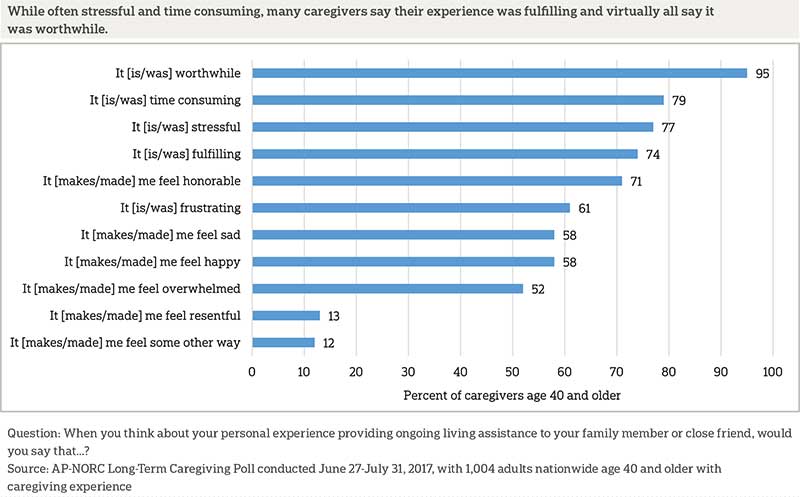

- Virtually all caregivers say the caregiving experience was worthwhile (95 percent) despite more than 3 in 4 characterizing their experiences as stressful or time consuming.

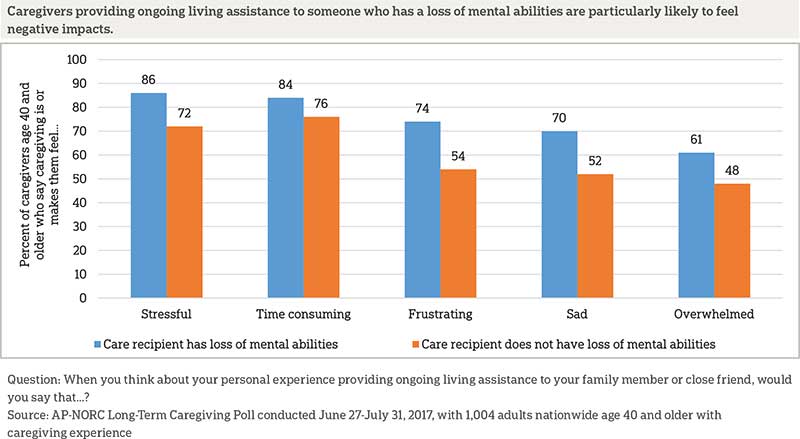

- Those caring for someone with a loss of memory or mental abilities are more likely than those caring for someone without these conditions to say caregiving is stressful, time consuming, frustrating, and makes them feel overwhelmed and sad.

- Controlling for other demographic factors, higher education and greater income are associated with describing caregiving in more negative terms. Those with a bachelor’s degree or higher are less likely than those with less education to say caregiving is fulfilling or makes them happy and are more likely to say it makes them feel resentful. Similarly, those with household incomes of at least $50,000 per year are more likely to say caregiving is stressful, frustrating, or makes them feel sad.

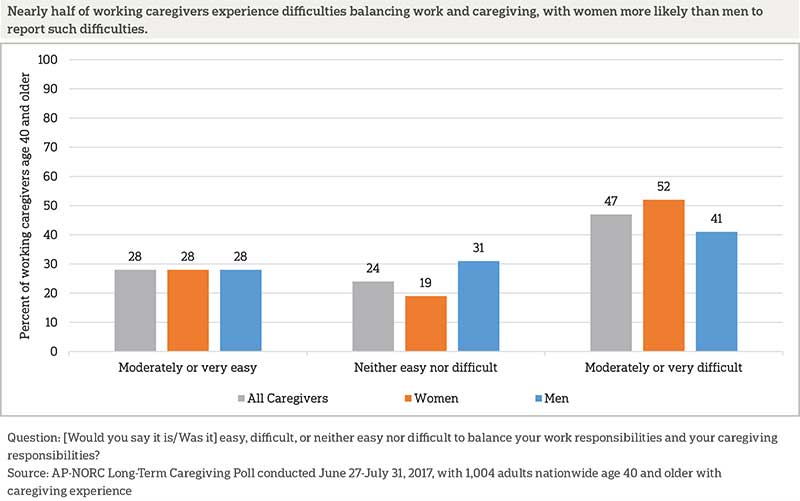

- Most caregivers have worked at the same time while providing care, and 47 report difficulties balancing work and caregiving responsibilities.

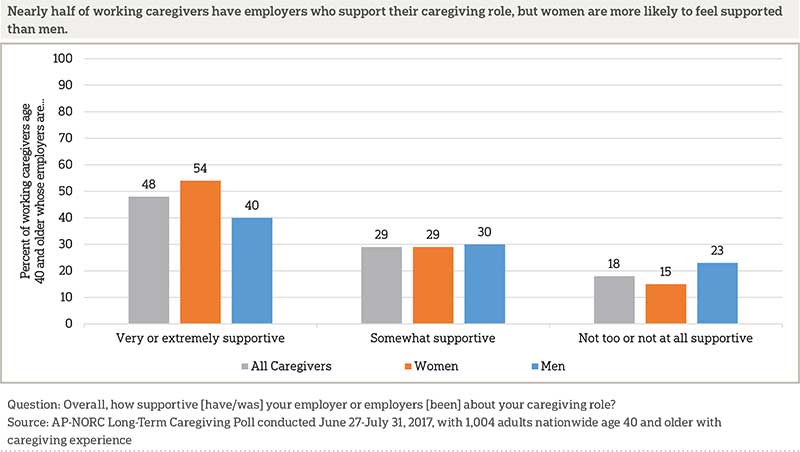

- Women are more likely than men to say their employers are very or extremely supportive of their role as a caregiver (54 percent vs. 40 percent), whereas working male caregivers are more likely to report their employers are not at all supportive.

- Seventy percent of working caregivers have missed work to provide care to an aging friend or family member, and while most use their sick, vacation, or personal time, many have also taken unpaid leave to provide this care.

- Working caregivers whose employers do not offer paid time off (PTO) are more likely than those whose employers do offer PTO to switch from full-time to part-time to provide care (13 percent vs. 4 percent) and to quit their jobs to provide care (14 percent vs. 6 percent).

- Some working caregivers have experienced serious repercussions at work because they needed to provide care to an aging loved one: 10 percent were treated differently by management or coworkers, 8 percent say they were excluded from further job growth opportunities, and 7 percent had their roles or responsibilities changed. In rare cases, some even report being fired or asked to resign as a result of their caregiving duties.

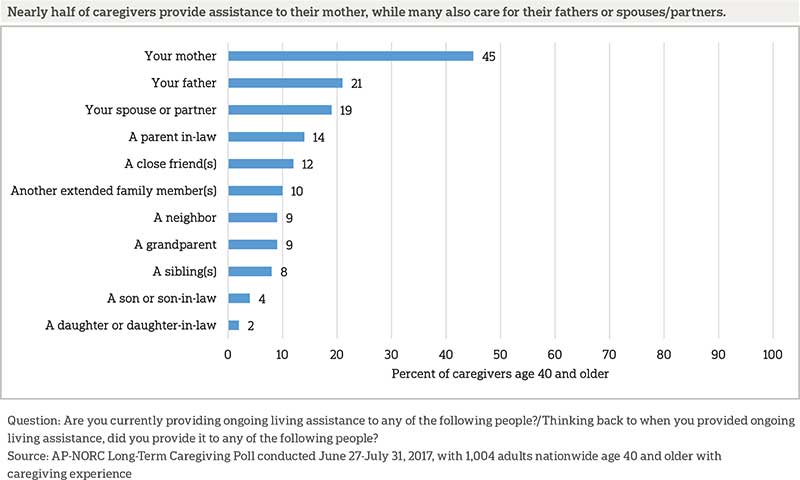

- Among those who have provided care in the past year, over one-quarter provide care to more than one person. The majority of caregivers (63 percent) provide care for an aging parent or parent-in-law.

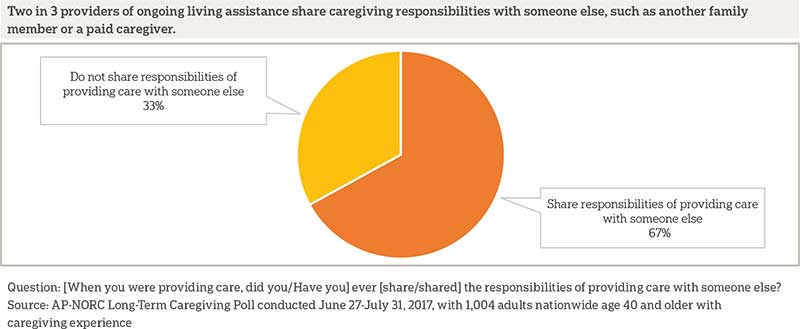

- Two-thirds of caregivers share caregiving responsibilities with at least one other person—most often with either a sibling or a paid caregiver. But fully one-third take on the caregiving role on their own.

- Seventy-seven percent say there is another family member or friend who can temporarily take on caregiving responsibilities to provide a break, but few have access to formal respite care options for their loved one.

Additional information, including the survey’s complete topline findings, can be found on The AP-NORC Center’s long-term care project website at www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Section 1: Caregivers’ Experiencesꜛ

American Caregivers Are Providing Significant Levels of Assistance for a Variety of Conditions, and They Are Not Getting Much Training to Do So. ꜛ

Caregivers help older loved ones with functional limitations due to different types of mental and physical conditions. The loss of mental abilities or memory, short-term physical conditions, long-term physical conditions, and other conditions can all result in the need for ongoing living assistance, and caregivers were asked whether or not the person they care or cared for needed assistance because of limitations associated with each of those four types of conditions5,6

Forty-six percent say the person they care for needs help because of limitations from more than one type of condition, but long-term physical conditions like diabetes, loss of vision, or loss of mobility are the most common (59 percent). For 36 percent of caregivers, the person they care for needs help because of loss of memory or other mental abilities, such as Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. Thirty-one percent provide care because of short-term physical conditions or diseases, such as pneumonia or an injury from an accident. Thirty-five percent provide help because of some other type of condition.

The job of a caregiver often involves helping with a wide variety of daily living activities. From a list of 16 types of ongoing living assistance like help with cooking, getting around inside the home, administering medication, and managing injections, 50 percent say they help with 6 to 10 tasks, and another 28 percent help out with 11 or more. Those who care for a spouse perform even more tasks than those who don’t: 42 percent say they help out with at least 11 types of ongoing living assistance compared to 25 percent of those who don’t care for a spouse who say the same.

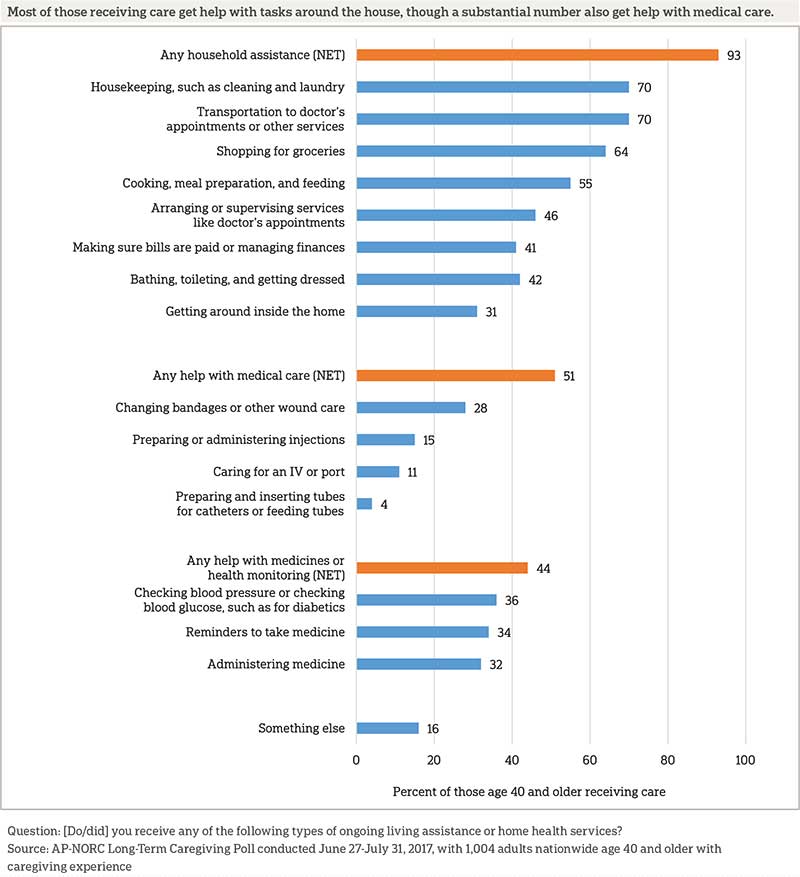

For nearly all caregivers, providing care for an older loved one means helping out around the house, while more than three-quarters help with tasks related to medication or health monitoring and nearly half provide medical care.

The condition of the person being cared for is related to the types of assistance caregivers provide. Those caring for someone with the loss of memory or other mental abilities are more likely than those who care for someone without memory loss to provide help with medicine and health monitoring (83 percent vs. 73 percent). Those caring for someone with a short-term physical condition are more likely to help with medical care like changing bandages than those who care for someone who does not have a short-term condition (58 percent vs. 43 percent). Those providing care to a spouse are also more likely than those who care for someone else to provide help with medicine and health monitoring (91 percent vs. 74 percent) or other medical care (60 percent vs. 45 percent).

Despite all the help they provide, few caregivers have received formal training in how to provide ongoing living assistance. In total, just 31 percent of caregivers have had any sort of formal training, including formal training from a doctor, a class on senior care, or professional experience in caregiving. Thirty-seven percent of those whose duties included help with bathing and toileting and those whose duties included getting around the house had any kind of formal training. Those whose duties include medical tasks are more likely to have training, but even among this group many do not. Less than half (46 percent) have formal training and 54 percent do not. Similarly, 48 percent of those who check blood pressure or blood glucose have some kind of formal training.

The most common method for learning how to provide care is learning on the job or teaching themselves how to do it. Most caregivers learned how to provide care in multiple ways, with 77 percent naming more than one method, including 57 percent who named three or more.

Those who provide medical care, such as changing bandages or preparing and administering injections, are more likely to take multiple approaches to learning. Caregivers who provide help with medical care are more likely than those who do not help with medical care to have learned through three or more methods (73 percent vs. 41 percent). While those who provide medical care are more likely than other caregivers to receive formal training from a health care professional, only 38 percent have done so. And, although they are more likely to do so than those who do not provide medical care, just 19 percent have taken a class on senior care. They are also more likely than those who do not provide medical care to talk to a health care professional (77 percent vs. 46 percent), talk to friends or family who have been caregivers (39 percent vs. 28 percent), and search online (33 percent vs. 19 percent).

Caregivers who assist with medicines and health monitoring, such as checking blood pressure or blood glucose, are also more likely to use some learning methods. Those who provide help with medicines and health monitoring are more likely than those who do not to talk to a health care professional (67 percent vs. 40 percent) and to have professional experience providing care (7 percent vs. 2 percent). They are also more likely than those who do not help with medicines or health monitoring to use three or more approaches to learning (61 percent vs. 41 percent).

Those caring for someone with the loss of memory or other mental abilities are more likely than those who care for someone without memory loss to seek out several types of education, including talking to a health care professional (68 percent vs. 56 percent), talking to friends or family who have been caregivers (40 percent vs. 30 percent), searching for information online (32 percent vs. 22 percent), or reading a newspaper, magazine, or book (27 percent vs. 13 percent). Those caring for someone with a short-term physical disability, however, are more likely than those caring for someone with other conditions to take a class on providing care for seniors (19 percent vs. 10 percent).

Perhaps reflecting the lack of formal training for many, the majority of caregivers say they feel undertrained. Twenty-five percent say they only received some of the training they needed to provide care, 14 percent say they received hardly any of the training they needed and 15 percent say they received none of it. Forty-seven percent say they received all or most of the training they needed to provide care. Those caring for someone with the loss of memory or other mental abilities, a short-term physical condition, and a long-term physical condition all feel similarly prepared, as do those who provide medical forms of care to a loved one.

The Caregiving Experience Is Overall Positive, But Also Stressful.ꜛ

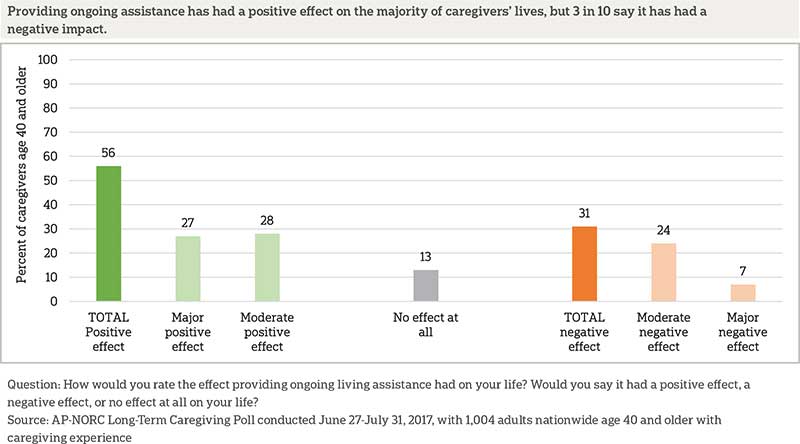

While some caregivers say caregiving has a positive impact on their life, others say the effect is negative. A majority of caregivers do say providing care has a positive impact; however, some feel that providing ongoing living assistance has a major or minor negative impact on their lives, and a small proportion say it has no impact at all.

Caregivers find that the experience of providing care is often difficult but ultimately worthwhile. Virtually all caregivers say the experience was worthwhile, despite more than 3 in 4 characterizing their experiences as stressful or time consuming. Majorities also find themselves overwhelmed, frustrated, or sad.

Still, nearly as many say caregiving is fulfilling or that it makes them feel honorable. About 6 in 10 report that the experience makes them feel happy or sad. Fewer say the experience of caregiving makes them feel resentful or some other way.

The caregiver’s relationship to the care recipient also impacts feelings towards caregiving. Similar to a prior AP-NORC analysis,7 the survey finds that those providing care to a spouse are more likely to say they feel the experience is stressful (86 percent) than those caring for someone other than a spouse (75 percent). Caregivers providing ongoing assistance to a parent are more likely than others to say it is overwhelming (57 percent vs. 45 percent).

Caregivers who provide assistance to those with deteriorating mental abilities or long-term conditions feel more negative about their caregiving experiences. Those caring for someone with a loss of mental abilities, such as Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, are more likely than those caring for others without those conditions to say caregiving is stressful, time consuming, frustrating, and makes them feel overwhelmed and sad. Similarly, caregivers providing assistance to someone with a long-term condition, disease, or disability are more likely than others to say they feel it’s frustrating (65 percent vs. 55 percent) or that they feel resentful (15 percent vs. 9 percent).

Controlling for other demographic factors, higher education and greater income are associated with describing caregiving in more negative terms. Those with a bachelor’s degree or higher are less likely than those with some college or less to say caregiving is fulfilling (65 percent vs. 78 percent) or makes them happy (46 percent vs. 64 percent), and they are more likely to say it makes them feel resentful (19 percent vs. 10 percent). Similarly, those with household incomes of at least $50,000 per year are more likely than those with incomes of less than $50,000 per year to say caregiving is stressful (84 percent vs. 71 percent), frustrating (67 percent vs. 55 percent), or makes them feel sad (65 percent vs. 52 percent).

Gender also plays a role in feelings towards caregiving. Women, who outnumber men as caregivers and are more susceptible to caregiver burden,8 are more likely than men to say providing long-term care makes them feel overwhelmed and resentful. While 6 in 10 women say caregiving makes them feel overwhelmed, a minority (41 percent) of men say the same. Women are also twice as likely as men to say providing ongoing living assistance makes them feel resentful (16 percent vs. 7 percent).

Working While Caregiving Is A Precarious Balance.ꜛ

Most caregivers balance caregiving responsibilities while they are working, with 64 percent providing care at some point while employed. Caregivers who work report difficulties balancing work and caregiving responsibilities. In particular, women who work while providing care report greater difficulties balancing the two roles. About half of female caregivers who work describe it as moderately or very difficult to balance their work and caregiving responsibilities.

Most working caregivers (59 percent) have discussed their caregiving role with a coworker, but fewer (45 percent) working caregivers have discussed their caregiving role with a supervisor, and just 15 percent have discussed it with someone in human resources.

Fifty-seven percent of working caregivers are offered paid time off (PTO) for vacation by their employer, but 41 percent are not. Caregivers whose employers offer PTO are more likely to talk to others at work about their role as a care provider compared to those whose employers do not offer PTO. Caregivers with PTO are more likely to talk to a coworker (70 percent vs. 45 percent), a supervisor (58 percent vs. 26 percent), and someone in human resources (19 percent vs. 9 percent) about their role as a care provider.

Those caring for someone with loss of memory or other mental abilities are more likely than those caring for someone without loss of mental abilities to talk to a coworker about their caregiving role (66 percent vs. 55 percent), but they are no more likely to talk to a supervisor or someone in human resources.

Working caregivers have received varying degrees of support from their employers, and women and men perceive differences in the level of support they get. Women are more likely than men to say their employers are very or extremely supportive. On the other hand, men are more likely to feel their employers are not at all supportive.

Caregivers whose employers offer PTO are more likely to say their employer is very or extremely supportive of their caregiving role than are those whose employers do not offer PTO (57 percent vs. 37 percent) and are less likely to say their employer is not too or not at all supportive (14 percent vs. 25 percent).

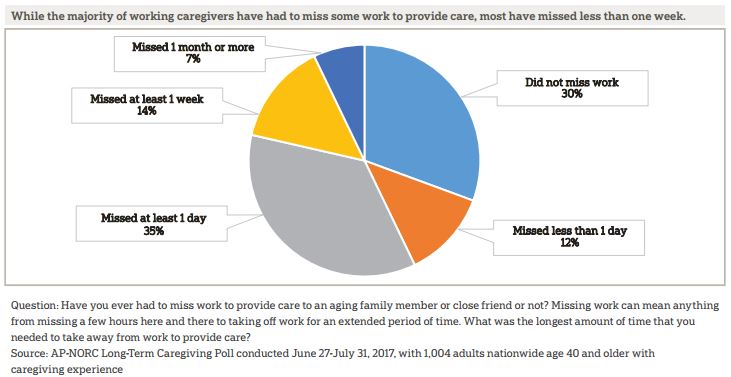

Seventy percent of working caregivers have had to miss work to provide care. Among those who have missed work, the majority had to miss less than one week.

Women are more likely than men to miss work to provide care (74 percent vs. 63 percent). And, 78 percent of those with household incomes of $100,000 or more missed work to provide care, compared to 65 percent of those with household incomes of less than $50,000. Seventy-one percent of those with household incomes between $50,000 and $100,000 missed work to provide care.

Working caregivers report using different means for taking time off from work to provide care. The majority of working caregivers who have missed work to provide care, 73 percent, use their sick, vacation, or personal time when they need to take time off work to provide care. Fully 39 percent also take unpaid leave to provide care. In addition, 10 percent take paid leave for caregivers and receive full pay and another 2 percent take paid leave for caregivers and receive partial pay. Eight percent take time off in some other way and 5 percent use flexible hours to provide care or they are self-employed.

Thinking about the care needs of their loved ones, 65 percent of caregivers who missed work to provide care feel they had enough time off work, but 34 percent say it was not enough time. Caregivers who are in good or better health themselves are more likely than those who are in fair or poor health to say that it was enough time off work to provide care (70 percent vs. 49 percent).

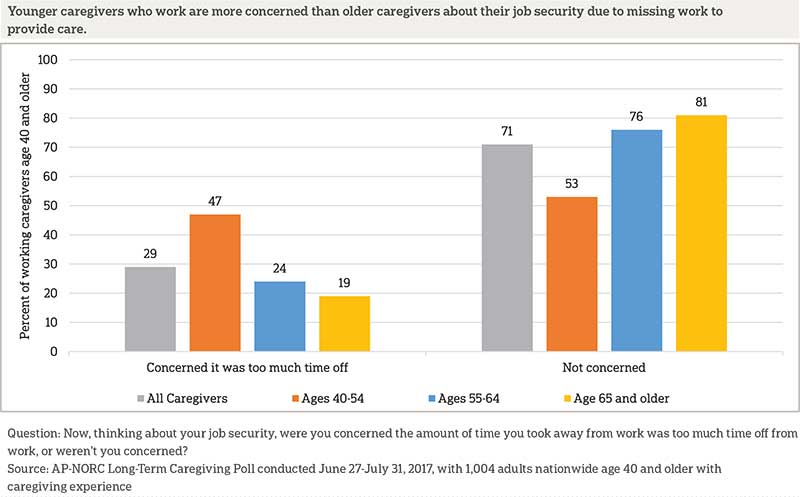

Most caregivers who have missed work to provide care say they are not concerned about their job security due to the amount of time they had to take off, but 29 percent are. Younger caregivers are more likely to be concerned about taking too much time off work to provide care. Nearly half of caregivers age 40 to 54 are concerned about the amount of time they took off work, compared to fewer than a quarter of those age 55 to 64 or age 65 and older.

Some working caregivers change their schedules at work in order to provide care to loved ones. Thirty-eight percent of working caregivers have changed the days or hours they work to provide care and 8 percent have switched from full-time to part-time schedules. Other caregivers decide to leave the workforce earlier than planned. Nine percent have quit a job and 10 percent have retired early in order to provide care to an aging friend of family member.

Those whose employers do not offer PTO are more likely to switch from full-time to part-time to provide care (13 percent vs. 4 percent) and to quit their jobs to provide care (14 percent vs. 6 percent) than those whose employers do offer PTO. Women are also more likely than men to quit their jobs to provide care (13 percent vs. 3 percent).

Some working caregivers report experiencing serious repercussions at work because they need to provide care to an aging loved one: 10 percent were treated differently by management or coworkers, 8 percent say they were excluded from further job growth opportunities, and 7 percent had their roles or responsibilities changed. In rare cases, some even report being fired or asked to resign as a result of their caregiving duties.

Who Are American Caregivers and for Whom Are They Providing Care?ꜛ

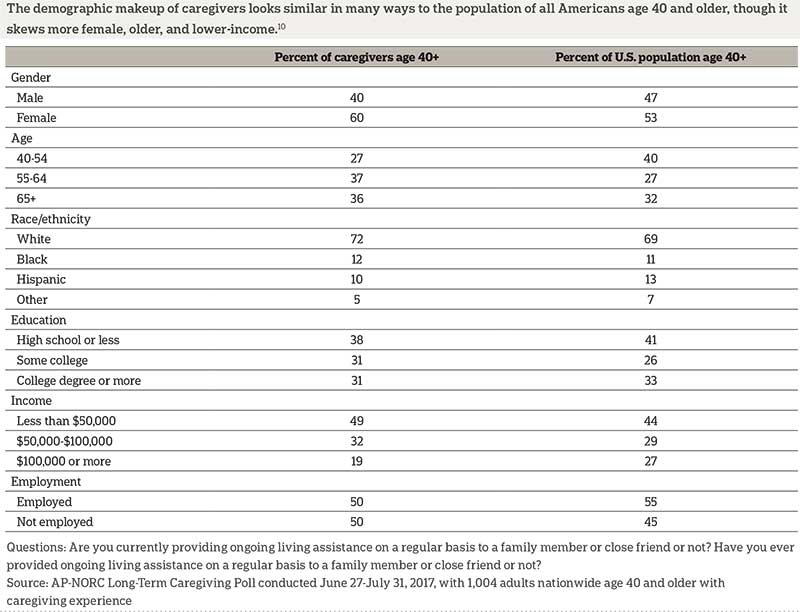

Among the population of caregivers age 40 and older, the average age is 61, with 27 percent age 40-54, 37 percent age 55-64, 26 percent age 65-74, and 9 percent age 75 and older, skewing slightly older than Americans age 40 and older overall. Six in 10 caregivers are women. Caregivers are less likely than the broader population age 40 and older to have an income of $100,000 or more. This may be partially due to slightly fewer caregivers being in the workforce compared to the overall population age 40 and older. Most are white, roughly reflecting the overall population of Americans age 40 and older. Education levels among caregivers also reflect those of Americans age 40 and older. They are also about as healthy as Americans age 40 and older overall, with 79 percent describing their own health as good or better, compared with 78 percent who said the same in the 2017 Long-Term Care Trend Poll.9

10

10

Many provide care to more than one person at a time. Among those age 40 and older with any experience providing care, 45 percent have not provided care to anyone in the past year, though they have in the past. For those who have provided care in the past year, 72 percent have provided care to one person, while 18 percent say they provided care to two people and 10 percent have provided care to three or more.

Caregivers provide help to a range of family members and friends, but the majority (63 percent) care for a parent or parent-in-law. They are particularly likely to care for their mother, though many care for their father or parent in-law. Nearly 2 in 10 care for a spouse or partner, while about 1 in 10 care for a close friend, a neighbor, a grandparent, a sibling, or another family member. Fewer (6 percent) provide ongoing living assistance to a child.

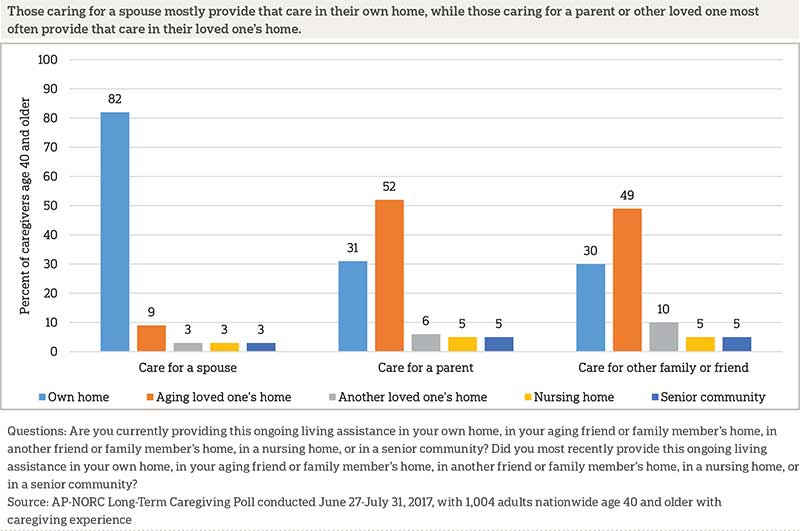

Forty-four percent of caregivers provide care in the home of their aging friend or family member, while 39 percent provide care in their own home. Just 7 percent provide care in a different friend or family member’s home, 5 percent provide care in a nursing home, and 4 percent provide care in a senior community.

Where care is provided depends on who the caregiver is providing care to. Those providing care to a spouse most often provide it in their own home, while those taking care of a parent most often provide it in their parent’s home. Those providing care to another relative or friend most often provide care in their aging loved one’s home.

Proximity is important for many caregivers, and 18 percent have moved in order to be closer to the person they provide care to. Those who earn $100,000 a year or more are less likely to have moved to provide care than those who earn less (9 percent vs. 20 percent).

Those who moved closer to the person they provide care to may be making their lives easier in the future, as many caregivers end up in a caregiving role for an extended period of time. Forty-six percent say they have provided care for more than two years. Another 24 percent have provided care for one to two years. Thirty percent have been providing care for less than a year.

Very few caregivers are paid for the care they provide. Just 9 percent have received some payment for providing care to a family member or friend, and 91 percent have not been paid. Those who provide care to someone other than a spouse or parent, however, are more likely than those who care for a spouse or parent to be paid (14 percent vs. 5 percent).

In the Majority of American Families, Caregiving Responsibilities Are Shared.ꜛ

While many caregivers describe their experience as difficult, only a minority have to provide this care entirely on their own. Most caregivers are able to share caregiving responsibilities with someone else, such as a family member or a paid caregiver. Still a third of caregivers shoulder these responsibilities on their own.

Those who work and provide care simultaneously are more likely to share responsibilities (72 percent), but a majority of those who do not work also have someone with whom to share responsibilities (56 percent). And although women make up the majority of caregivers, men are more likely than women to have someone else with whom to divide caregiving responsibilities (74 percent vs. 63 percent).

Who you provide care to also impacts the likelihood of sharing caregiving responsibilities with another person. Seventy-two percent of caregivers providing care to someone with long-term physical conditions, diseases, or disabilities—such as diabetes, loss of vision, or loss of mobility—share caregiving compared with 60 percent of those providing care to someone with other conditions.

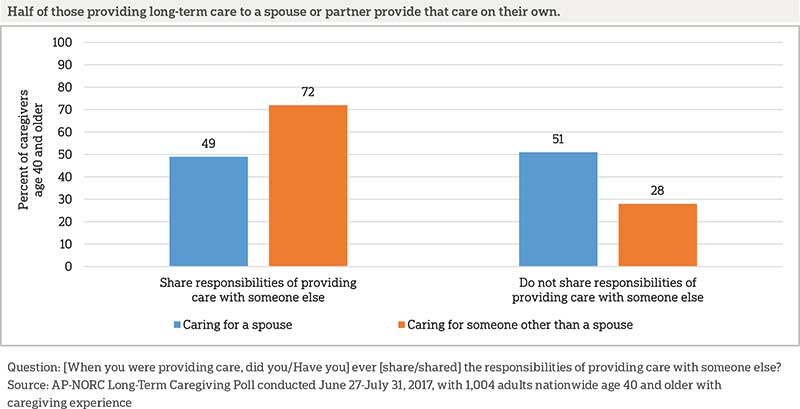

Those who care for a spouse, rather than a parent, family member, or some other person, are often left to provide care on their own. Fewer than half who care for a spouse share caregiving responsibilities compared with about 3 in 4 who care for someone other than a spouse.

Compared to those who share caregiving responsibilities with someone else, those who are the sole care provider are more likely to provide care in their own home (56 percent vs. 31 percent) and less likely to provide care in their loved one’s home (31 percent vs. 50 percent) or another friend or family member’s home (4 percent vs. 9 percent).

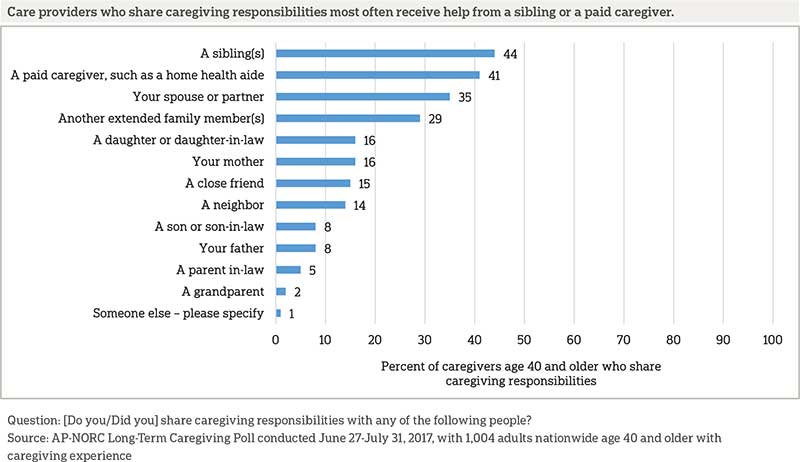

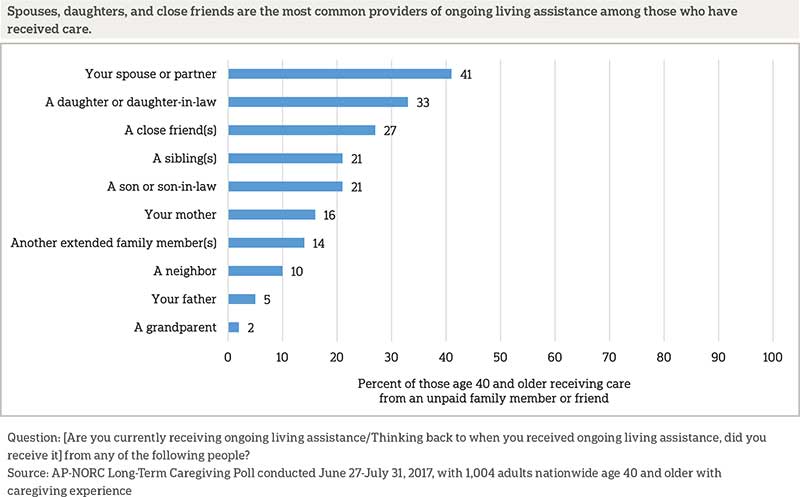

Of those who share caregiving with someone else, providers most frequently divide responsibilities with either a sibling or a paid caregiver. Another 3 in 10 split caregiving tasks with a spouse or partner or with another extended family member. Less than 2 in 10 share responsibilities with their mother, a daughter or daughter-in-law, a close friend, or a neighbor. Even fewer provide care with their father, a son or son-in-law, a parent-in-law, a grandparent, or with someone else.

As one might expect, those caring for a parent or parent-in-law are more likely than those caring for others to share responsibilities with a sibling (56 percent vs. 18 percent) or a spouse or partner (41 percent vs. 23 percent). More surprisingly, among those who share caregiving responsibilities, income does not impact whether or not the additional help is provided by a paid caregiver like a home health aide rather than a family member or friend. However, those providing care to someone with deteriorating mental abilities (50 percent vs. 35 percent) or a long-term condition (46 percent vs. 32 percent) are more likely to share responsibilities with a paid caregiver than those caring for others.

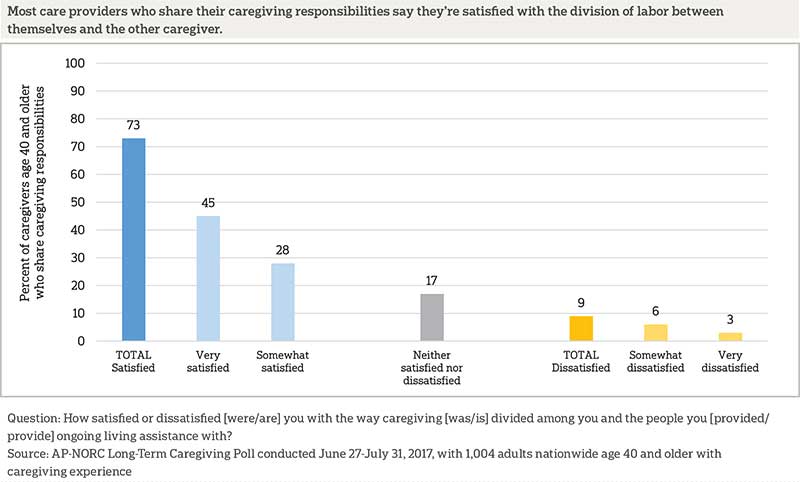

Overall, those who do share caregiving generally report being content with their arrangement. The level of satisfaction does not vary much by demographics, by the caregiving relationships, where the care occurs, or the types of health conditions that require a need for care.

Even if caregiving isn’t formally shared among multiple people, nearly all (85 percent) caregivers have access to at least one way to temporarily cover their caregiving responsibilities if they need to go away or take a break. This includes 71 percent who say there is another family member or friend who can temporarily take on caregiving responsibilities, 27 percent who cite the availability of a formal respite care program, and 17 percent who cite the availability of an adult day care center or community senior services for their loved one.

Section 2: Care Recipients’ Experiencesꜛ

Older Americans Receive Care for a Variety of Conditions and Get Help with Daily Living and Medical Tasks.ꜛ

Among older adults who receive care, the majority suffer from long-term physical conditions, diseases, or disabilities, such as diabetes, loss of vision, or loss of mobility (64 percent). Many (40 percent) suffer from short-term physical conditions, and few (12 percent) of those surveyed suffer from loss of memory or other mental abilities, such as Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. Thirty-eight percent say they need care for something else.11 Forty-eight percent say they need care due to more than one of these types of conditions.

Many have received care for at least a year: 23 percent have been receiving or did receive care for one to two years and another 42 percent for more than two years. Thirty-four percent say their care has lasted less than a year. Those receiving care from a spouse have been receiving it for less time; they are less likely to have been receiving care for more than two years (34 percent vs. 50 percent), and more likely to have been receiving care for less than a year (44 percent vs. 27 percent).

Those receiving care get assistance with many aspects of their daily lives. Nearly all receive help with daily tasks around the house, while more than half are assisted with medical care such as changing bandages or preparing or administering injections. More than 4 in 10 are helped with medicine or health monitoring either through reminders to take medicine or administering medicine, the latter which paid in-home caregivers cannot do in many states.12

Those receiving care due to memory loss are more likely than those who are not to receive help with medicine (92 percent vs. 38 percent), and those suffering from a short-term physical condition are more likely than those who are not to be receiving help with medical procedures like changing bandages (63 percent vs. 44 percent).

Most Receive Care in Their Own Home, and Many Rely on Family Members to Provide Care at No Cost.ꜛ

Most receiving care get that care in their own home (80 percent), while 10 percent receive it in a friend or family member’s home. Eight percent mostly receive care in a senior community and just 2 percent of those surveyed say it was in a nursing home. Less than half (44 percent) live in the same home with their caregiver. But few (14 percent) have moved to be closer to a caregiver.

Among those who receive care in home settings, 62 percent receive it from an unpaid family member and 27 percent from an unpaid friend. Forty-six percent receive care from a paid caregiver.

Of those who receive care in a home setting from a family member or friend, 4 in 10 receive care from a spouse or partner, and a similar number receive care from one of their children or children-in-law. More receive help from their daughters or daughters-in-law than their sons or sons-in-law, however. Nearly 3 in 10 are cared for by a close friend, and 2 in 10 get help from a sibling. Even among these recipients, all of whom are age 40 and older, 16 percent get help from their mother and 5 percent get help from their father. About 1 in 10 get care from other extended family members or a neighbor.

Among those who have received care at any point, half have received it from just one person, 22 percent say two people have shared responsibilities, and 23 percent say three or more people have done so. Those in shared caregiving situations are overwhelmingly happy with how their care is divided; 73 percent are very satisfied with the division of care and 18 percent are somewhat satisfied. Just 4 percent are dissatisfied and 5 percent are neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. There is little difference in satisfaction with how care is divided across types of conditions requiring care, who is providing the care, what type of care is provided, or where care is provided.

Those with Experiences with Person-centered Care Practices Say Those Practices Have Improved Their Care.ꜛ

This survey asked questions about “person-centered care,” an approach to health care and supportive services that allows individuals to take control of their own care by specifying preferences and outlining goals that will improve their quality of life. Ways a care recipient can experience person-centered care include having a single care manager who serves as a point of contact and can coordinate all aspects of care and having an individualized care plan designed to take into account the patient’s personal goals and preferences. Those who regularly receive care from two or more doctors as part of their own long‑term care or the care of loved ones were asked if their doctors engage in these person-centered care practices.

Four in 10 of those with current long-term care experience as either a recipient or provider and who regularly receive care from two or more doctors have a single care manager who serves as a point of contact and coordinates all aspects of care. A similar proportion (38 percent) of those currently providing or receiving long-term care have an individualized care plan designed to take into account their personal goals and preferences.

The vast majority of people who receive person-centered care think it improves their care, but those who do not receive these services are unsure about their value. Those who have a single care manager or who provide care to someone who has one generally feel it has improved their care; 68 percent say having a single care manager has improved their care a lot and 25 percent say it has improved their care a little. Of those who do not have a single care manager, 31 percent believe it would improve their care a lot, another 37 percent say it would improve care a little, and 30 percent do not think having a care manager would improve their care at all.

Similarly, those with an individualized care plan or who provide care to someone who has one say it has improved care; 56 percent say having an individualized care plan has improved care a lot, and 36 percent say it has improved care a little. Among those who do not have an individualized care plan, 40 percent think it would improve care a lot, 32 percent think it would improve care a little, and 26 percent believe it would not improve care at all.

About the Studyꜛ

Study Methodology

This study, funded by The SCAN Foundation, was conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Data were collected using AmeriSpeak®, NORC’s probability-based panel designed to be representative of the U.S. household population. During the initial recruitment phase of the panel, randomly selected U.S. households were sampled with a known, non-zero probability of selection from the NORC National Sample Frame and then contacted by U.S. mail, email, telephone, and field interviewers (face-to-face). The panel provides sample coverage of approximately 97% of the U.S. household population. Those excluded from the sample include people with P.O. Box only addresses, some addresses not listed in the USPS Delivery Sequence File, and some newly constructed dwellings. Of note for this study, the panel would also exclude recipients of long-term care who live in institutional types of settings, such as skilled nursing facilities or some types of nursing homes. Staff from NORC at the University of Chicago, The Associated Press, and The SCAN Foundation collaborated on all aspects of the study.

Interviews for this survey were conducted between June 27 and July 31, 2017, with adults age 40 and older with experience with long-term care representing the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Panel members were randomly drawn from AmeriSpeak and invited to complete a screener to determine their eligibility for the survey. In addition, panelists who completed the 2017 Long-Term Care Trend Poll and answered that they had experience with long-term care were invited to complete the screener. Those with current or past experience as a provider or receiver of long-term care in the screener were invited to the survey, and 1,004 completed the survey—663 via the web and 341 via telephone. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish, depending on respondent preference. Respondents were offered a small monetary incentive ($5) for completing the survey.

The screener completion rate is 47.0 percent, with an incidence rate of 54.9 percent. The final stage completion rate is 37.2 percent, the weighted household panel response rate is 31.4 percent, and the weighted household panel retention rate is 91.1 percent, for a cumulative AAPOR response rate 3 of 13.2 percent. The overall margin of sampling error is +/- 3.7 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level, including the design effect. For the care providers, the margin of sampling error at the 95 percent confidence level is +/- 4.2 percentage points. For the care recipients, the margin of sampling error at the 95 percent confidence level is +/- 7.4 percentage points.

Once the sample has been selected and fielded, and all the study data have been collected and made final, base sampling weights for the selected sample were adjusted for screener nonresponse, and then a poststratification process is used to adjust for any survey nonresponse. Poststratification variables included age, gender, census division, race/ethnicity, and education. Population totals for U.S. adults age 40 and older who have experience with long-term care were obtained using the screener nonresponse adjusted weight for all eligible respondents from the screener questions. At the final stage of weighting, any extreme weights were trimmed based on a criterion of minimizing the mean squared error associated with key survey estimates, and then, weights re-raked to the same population totals. The weighted data reflect the U.S. population of adults age 40 and over who have experience with long-term care.

All analyses were conducted using STATA (version 14), which allows for adjustment of standard errors for complex sample designs. All differences reported between subgroups are at the 95 percent level of statistical significance, meaning that there is only a 5 percent (or less) probability that the observed differences could be attributed to chance variation in sampling. Additionally, bivariate differences between subgroups are only reported when they also remain robust in a multivariate model controlling for other demographic and socioeconomic covariates.

A comprehensive listing of all study questions, complete with tabulations of top-level results for each question, is available on The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research long-term care website: www.longtermcarepoll.org.

Contributing Researchers

From NORC at the University of Chicago

Jennifer Benz

Jennifer Titus

Dan Malato

Liz Kantor

Alexander Agadjanian

Trevor Tompson

From The Associated Press

Emily Swanson

About The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research

The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research taps into the power of social science research and the highest-quality journalism to bring key information to people across the nation and throughout the world.

- The Associated Press (AP) is the world’s essential news organization, bringing fast, unbiased news to all media platforms and formats.

- NORC at the University of Chicago is one of the oldest and most respected, independent research institutions in the world.

The two organizations have established The AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research to conduct, analyze, and distribute social science research in the public interest on newsworthy topics, and to use the power of journalism to tell the stories that research reveals.

The founding principles of The AP-NORC Center include a mandate to carefully preserve and protect the scientific integrity and objectivity of NORC and the journalistic independence of AP. All work conducted by the Center conforms to the highest levels of scientific integrity to prevent any real or perceived bias in the research. All of the work of the Center is subject to review by its advisory committee to help ensure it meets these standards. The Center will publicize the results of all studies and make all datasets and study documentation available to scholars and the public.

Footnotesꜛ

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. The Basics.

http://longtermcare.gov/the-basics/ꜛ

2. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing Research Brief.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/long-term-services-and-supports-older-americans-risks-and-financing-research-briefꜛ

3. Long-Term Care in America: Views on Who Should Bear the Responsibility and Costs of Care.

https://longtermcarepoll.org/PDFs/LTC%202017/AP-NORC%20Long-Term%20Care%20Poll%202017.pdfꜛ

4. Those who have both provided and received care are categorized as receivers in this analysis and report. ꜛ

5. Respondents were provided with the following definition of ongoing living assistance: “Some people need ongoing living assistance as they get older. This assistance can be help with things like keeping house, cooking, bathing, getting dressed, getting around, paying bills, remembering to take medicine, or just having someone check in to see that everything is okay. This help can happen at your own home, in a family member’s home, in a nursing home, or in a senior community. And, it can be provided by a family member, a friend, a volunteer, or a health care professional.” ꜛ

6. Ongoing living assistance could be current or in the past, and question wording was adjusted accordingly. The questionnaire logic specified that present tense was displayed for current providers/recipients while past tense was displayed for former providers/recipients. For the purposes of this report, we refer to caregiving in the present tense.ꜛ

7. The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. 2014. Long-Term Care in America: Expectations and Reality.

https://www.longtermcarepoll.org/Pages/Polls/Long-Term-Care-2014.aspxꜛ

8. Gonyea, JG, Paris R, and de Saxe Zerden, L. (2008). Adult daughters and aging mothers: The role of guilt in the experience of caregiver burden. Aging and Mental Health 12.5: 559-567.ꜛ

9. The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. 2017. Long-Term Care in America: Views on Who Should Bear the Responsibilities and Costs of Care.

https://longtermcarepoll.org/Pages/Polls/Long-Term-Care-in-America-Views-on-Who-Should-Bear-the-Responsibilities-and-Costs-of-Care.aspxꜛ

10. Population estimates for gender, age, race, and education were obtained from the February 2017 Current Population Survey. Household income was obtained from the 2015 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.ꜛ

11. The care recipients surveyed are likely a subgroup of all older adults who receive care. Those with more advanced memory loss or dementia or those with extreme disabilities that prevent them from taking a survey are likely not able to consent to be AmeriSpeak Panelists and thus complete surveys.ꜛ

12. S.C. Reinhard, E. Kassner, A. Houser, K. Ujvari, R. Mollica, and L. Hendrickson. 2014. Raising Expectations, 2014: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers. AARP, Commonwealth Fund, and SCAN Foundation.

http://www.longtermscorecard.org/2014-scorecardꜛ